There was a psychologist who lived in the early half of the 20th century by the name of Egon Brunswick.

Egon spent a good chunk of his career studying the field of perception and some of these findings are still relevant today.

If I was a more skilled writer, I would devote a good chunk of my next 6 months to Gladwell-izing Egon Brunswik and his ideas. There is enough good ideas in what I’ve read so far of his research, that it could probably make for a very compelling book.

Alas I am not a more skilled writer, so we will just stick to the highlights for now.

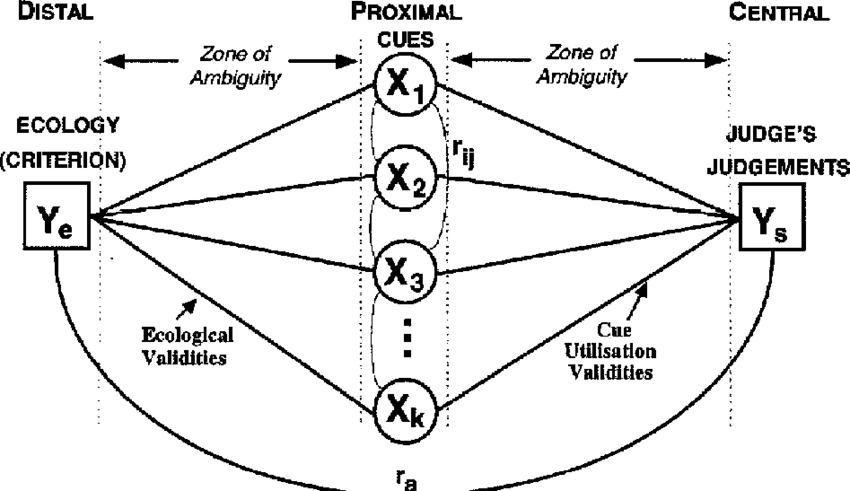

The Brunswik Lens Model

Egon proposed a model for perception called the Brunswik Lens Model.

It is very simple in it’s composition. But very powerful in it’s relevancy and as a mental model for how perception works.

Figure 1: Egon Brunswik’s Lens Model for perception

Figure 1: Egon Brunswik’s Lens Model for perception

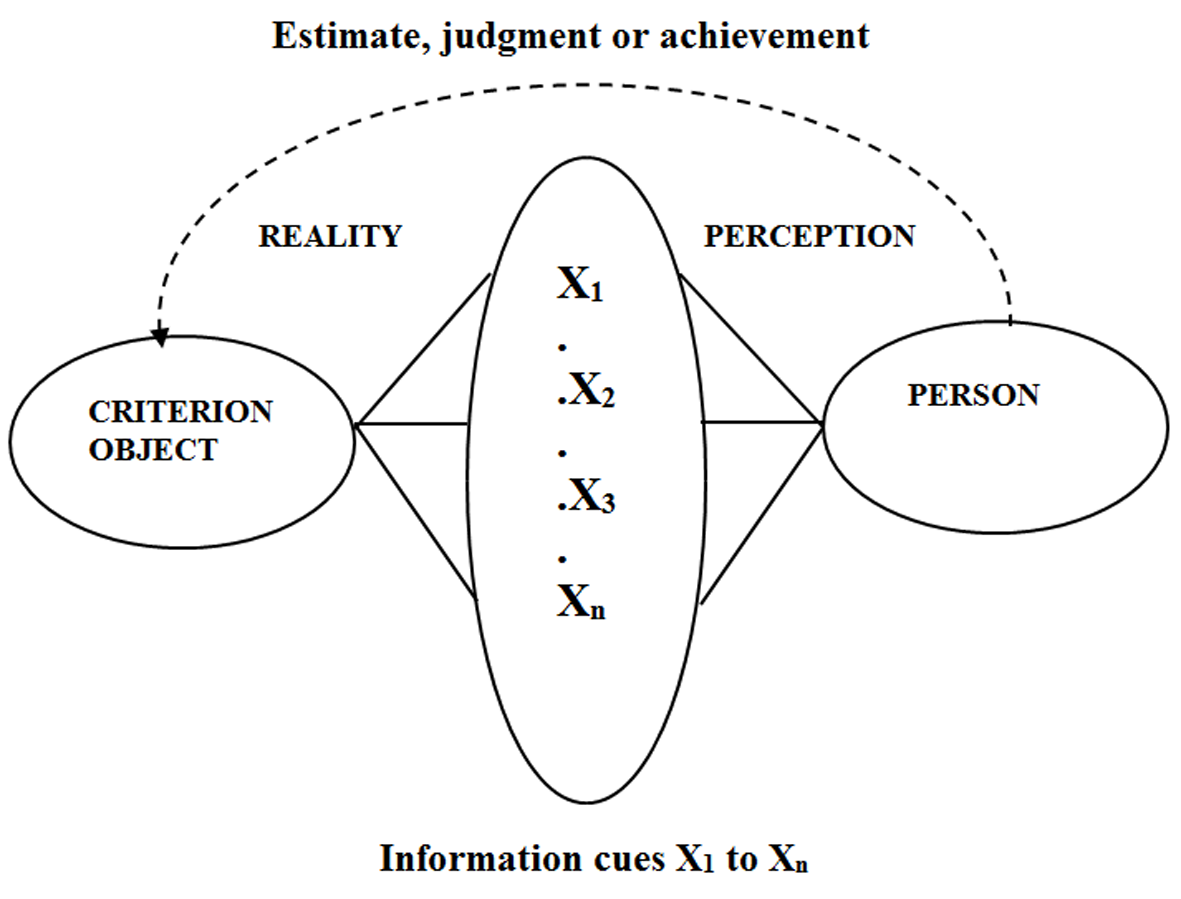

Figure 2: Simplified model to show the “lens” shape

Figure 2: Simplified model to show the “lens” shape

For the sake of understanding, let’s explain all the relevant terminology using the example: “How do I determine if a watermelon is ripe?”

The Lens is an intermediary between two sides.

On one side (traditionally the left-hand side) you have a “criterion” - this side represents reality. Everything on this side is the true nature of a thing. In our example, the watermelon is objectively either ripe or not ripe.

On the other side (right-hand side) you have a “judgment” - this side represents perception. Your perceived and rendered judgment about a thing. In our example, you will have to make some sort of judgment while at the grocer for whether the watermelon is ripe.

Within the lens are “proximal cues”. These are the facts or observable features of a matter. In our example, there are many types of tests for telling if a watermelon is ripe.

- Cue 1: The “Thump” Test: You tap the watermelon and listen for a deep, hollow sound. A dull thud might suggest it’s underripe or overripe.

- Cue 2: The Field Spot: You look for a creamy, yellowish spot on the bottom. A white or very pale green spot often indicates it was picked too soon.

- Cue 3: The Weight: You pick it up to see if it feels heavy for its size. A heavy watermelon is likely full of water and therefore ripe.

- Cue 4: The Appearance: You look for a dull, not shiny, surface. A shiny appearance can mean it’s not yet ripe. You also look for uniform shape and the absence of bruises.

There are also a set of cues which are available to you but you likely weren’t thinking about.

- Cue 5: It is a Tuesday morning.

- Cue 6: You are wearing tennis shoes today.

- Cue 7: It was raining outside.

You don’t pay attention to these irrelevant cues, because you have lived experience which says these factors can be discounted to 0 for the purposes of determing watermelon-ripeness. You assign 0 weight to them, or a “cue utilization value” of 0.

The thing is, you don’t actually know whether or not these factors or relevant. You assume not, because of your lived experience, but the cues by nature do have some corresponding weight on the ‘reality-side’ of your perceptual lens. This weight is called it’s “ecological validity”. You don’t actually know their true validity, although you can infer it. But it may be the case that when it rains, watermelons get ever so microscopically more ripe by some small factor.

At the end of running through this whole perceptual layer, you determine the watermelon to be ripe and you buy it and bring it home.

Judgement meets criterion when you open and taste the watermelon and determine if your perception was accurate. Was the watermelon ripe? This realization is referred to in the model as “achievement” - the degree to which your perception matched reality.

If your judgment was innaccurate, it means your cue utilization values were not calibrated to the same weight as their ecological validity. You overrated or underrated something. There also may be a whole host of inter-cue correlations that are a factor as well - cues don’t exist in isolation and may be inter-connected in surprising ways.

What does it mean … calibration

This perceptual model helps one to approach problems uniquely. Very rarely are there issues of correct and incorrect. People love being right and hate being wrong. And dialogue that happens at this level is usually combative and not healthy.

But rather almost everything can be approached from the higher order level of calibration. Do we agree on the set of proximal cues + what weights are we assigning to those cues + do those weights match the ecological validity of those cues.

This reduces down to some terminology which I have come to love - things being overrated or underrated.

Are you overrating some fact and underrating some other set of facts?

Another illustration

Take another common illustration of The Blind Men and the Elephant and interpret it through this Lens Model.

Figure 3: The Blind Men and the Elephant

Figure 3: The Blind Men and the Elephant

Each individual in this illustration has access to 1 cue which they are applying 100% weight to in order to determine what it is that they are feeling.

But their judgments are miscalibrated. Because the true ecological validities of those cues and the inter-cue correlations would point them to understand this thing they are feeling as an elephant.

In this case, the miscalibration is one of missing or ignoring cues, rather than down-rating an observed cue.

Observing and applying this in practice

Once you understand this Lens model, you will start to see it everywhere. You can even re-frame every modern discussion of biases and argumentative logical fallacies through this model.

Biases as a whole are a mostly un-useful concept. Because knowing about a bias does nothing to innoculate a person against that bias. Or help in discussions pointing out biases in others.

It is more useful to understand these as miscalibrations. And approach the discussion as both parties trying to get more calibrated.

The more valuable discussions for changing minds will take place by discussing the weights layer. Not the judgments or even cues layer.

“You are overrating/underrating [this cue] relative to [other cue]” is a lot more useful to start a discussion than “you are wrong and here’s why”.